In Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967), Alain Delon is like Michael Corleone at the end of the first Godfather. He’s dead-eyed and withdrawn; he lives to accomplish objectives that he spares nary a thought about; his girlfriend is an accessory, nothing more. Or is she? Although this is often called a great film, and Melville’s best—Army of Shadows, which features one of the most heart-rending executions in movie history, is a bona fide masterpiece—I don’t think it’s quite in the pantheon, or was meant to be. We see how Michael’s heart went cold; Le Samouraï is not—to borrow from Louis Malle’s The Fire Within—about a man with a heart to lose, but a brute force of nature. The title led me to expect an honorable killer, like Vito Corleone. The preface is from the book of Bushido: “There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai, unless it is that of the tiger of the jungle, perhaps.” The title should have been Le Tigre. But there’s more than one keyword in there, and they’re related. Delon lives in a scummy, unadorned flat. He’s not a disillusioned drinker like his film noir antecedents: He orders a whiskey and leaves it at the bar, and his apartment is stocked with Perriers. Only Perriers. “Solitude” implies an introspection that Delon lacks, but then there’s that tricky “perhaps.” That ties into his relationship with his girl (Nathalie Delon), who seems to think he needs her. And it ties into his relationship with the pianist (Caty Rosier); we’re never sure of her motives. Even if the story seems extremely basic, and Delon seems like a rather paltry assassin—from what we see of his methods, he should’ve been behind bars a long time ago—Melville doesn’t give us quite enough to know what’s going on, and that adds to the tension. Rosier gives him a look, a slight variant of her polite, professional-musician smile; is she an accomplice? Their relationship is ambiguous in a way that Delon’s personality is not. He’s impenetrable because he’s a genre construct, an existential given—and nobody underplays as stylishly as Delon. The mystery of his origins seems artificial, and that’s why the film never transcends its genre, as Army of Shadows and The Godfather do. But, as a thriller—as a commercial film rather than a work of art—it’s top notch, on par with something like the American Kiss of Death. It’s a French French Connection, with all the scrappy vigor of the New Wave. Delon may not be a samurai, but Melville cuts like one; like the swordsman in The Seven Samurai, it’s hard not admire his graceful craft.

In Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967), Alain Delon is like Michael Corleone at the end of the first Godfather. He’s dead-eyed and withdrawn; he lives to accomplish objectives that he spares nary a thought about; his girlfriend is an accessory, nothing more. Or is she? Although this is often called a great film, and Melville’s best—Army of Shadows, which features one of the most heart-rending executions in movie history, is a bona fide masterpiece—I don’t think it’s quite in the pantheon, or was meant to be. We see how Michael’s heart went cold; Le Samouraï is not—to borrow from Louis Malle’s The Fire Within—about a man with a heart to lose, but a brute force of nature. The title led me to expect an honorable killer, like Vito Corleone. The preface is from the book of Bushido: “There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai, unless it is that of the tiger of the jungle, perhaps.” The title should have been Le Tigre. But there’s more than one keyword in there, and they’re related. Delon lives in a scummy, unadorned flat. He’s not a disillusioned drinker like his film noir antecedents: He orders a whiskey and leaves it at the bar, and his apartment is stocked with Perriers. Only Perriers. “Solitude” implies an introspection that Delon lacks, but then there’s that tricky “perhaps.” That ties into his relationship with his girl (Nathalie Delon), who seems to think he needs her. And it ties into his relationship with the pianist (Caty Rosier); we’re never sure of her motives. Even if the story seems extremely basic, and Delon seems like a rather paltry assassin—from what we see of his methods, he should’ve been behind bars a long time ago—Melville doesn’t give us quite enough to know what’s going on, and that adds to the tension. Rosier gives him a look, a slight variant of her polite, professional-musician smile; is she an accomplice? Their relationship is ambiguous in a way that Delon’s personality is not. He’s impenetrable because he’s a genre construct, an existential given—and nobody underplays as stylishly as Delon. The mystery of his origins seems artificial, and that’s why the film never transcends its genre, as Army of Shadows and The Godfather do. But, as a thriller—as a commercial film rather than a work of art—it’s top notch, on par with something like the American Kiss of Death. It’s a French French Connection, with all the scrappy vigor of the New Wave. Delon may not be a samurai, but Melville cuts like one; like the swordsman in The Seven Samurai, it’s hard not admire his graceful craft.Friday, September 17, 2010

Le Samouraï

In Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967), Alain Delon is like Michael Corleone at the end of the first Godfather. He’s dead-eyed and withdrawn; he lives to accomplish objectives that he spares nary a thought about; his girlfriend is an accessory, nothing more. Or is she? Although this is often called a great film, and Melville’s best—Army of Shadows, which features one of the most heart-rending executions in movie history, is a bona fide masterpiece—I don’t think it’s quite in the pantheon, or was meant to be. We see how Michael’s heart went cold; Le Samouraï is not—to borrow from Louis Malle’s The Fire Within—about a man with a heart to lose, but a brute force of nature. The title led me to expect an honorable killer, like Vito Corleone. The preface is from the book of Bushido: “There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai, unless it is that of the tiger of the jungle, perhaps.” The title should have been Le Tigre. But there’s more than one keyword in there, and they’re related. Delon lives in a scummy, unadorned flat. He’s not a disillusioned drinker like his film noir antecedents: He orders a whiskey and leaves it at the bar, and his apartment is stocked with Perriers. Only Perriers. “Solitude” implies an introspection that Delon lacks, but then there’s that tricky “perhaps.” That ties into his relationship with his girl (Nathalie Delon), who seems to think he needs her. And it ties into his relationship with the pianist (Caty Rosier); we’re never sure of her motives. Even if the story seems extremely basic, and Delon seems like a rather paltry assassin—from what we see of his methods, he should’ve been behind bars a long time ago—Melville doesn’t give us quite enough to know what’s going on, and that adds to the tension. Rosier gives him a look, a slight variant of her polite, professional-musician smile; is she an accomplice? Their relationship is ambiguous in a way that Delon’s personality is not. He’s impenetrable because he’s a genre construct, an existential given—and nobody underplays as stylishly as Delon. The mystery of his origins seems artificial, and that’s why the film never transcends its genre, as Army of Shadows and The Godfather do. But, as a thriller—as a commercial film rather than a work of art—it’s top notch, on par with something like the American Kiss of Death. It’s a French French Connection, with all the scrappy vigor of the New Wave. Delon may not be a samurai, but Melville cuts like one; like the swordsman in The Seven Samurai, it’s hard not admire his graceful craft.

In Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967), Alain Delon is like Michael Corleone at the end of the first Godfather. He’s dead-eyed and withdrawn; he lives to accomplish objectives that he spares nary a thought about; his girlfriend is an accessory, nothing more. Or is she? Although this is often called a great film, and Melville’s best—Army of Shadows, which features one of the most heart-rending executions in movie history, is a bona fide masterpiece—I don’t think it’s quite in the pantheon, or was meant to be. We see how Michael’s heart went cold; Le Samouraï is not—to borrow from Louis Malle’s The Fire Within—about a man with a heart to lose, but a brute force of nature. The title led me to expect an honorable killer, like Vito Corleone. The preface is from the book of Bushido: “There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai, unless it is that of the tiger of the jungle, perhaps.” The title should have been Le Tigre. But there’s more than one keyword in there, and they’re related. Delon lives in a scummy, unadorned flat. He’s not a disillusioned drinker like his film noir antecedents: He orders a whiskey and leaves it at the bar, and his apartment is stocked with Perriers. Only Perriers. “Solitude” implies an introspection that Delon lacks, but then there’s that tricky “perhaps.” That ties into his relationship with his girl (Nathalie Delon), who seems to think he needs her. And it ties into his relationship with the pianist (Caty Rosier); we’re never sure of her motives. Even if the story seems extremely basic, and Delon seems like a rather paltry assassin—from what we see of his methods, he should’ve been behind bars a long time ago—Melville doesn’t give us quite enough to know what’s going on, and that adds to the tension. Rosier gives him a look, a slight variant of her polite, professional-musician smile; is she an accomplice? Their relationship is ambiguous in a way that Delon’s personality is not. He’s impenetrable because he’s a genre construct, an existential given—and nobody underplays as stylishly as Delon. The mystery of his origins seems artificial, and that’s why the film never transcends its genre, as Army of Shadows and The Godfather do. But, as a thriller—as a commercial film rather than a work of art—it’s top notch, on par with something like the American Kiss of Death. It’s a French French Connection, with all the scrappy vigor of the New Wave. Delon may not be a samurai, but Melville cuts like one; like the swordsman in The Seven Samurai, it’s hard not admire his graceful craft.Friday, September 10, 2010

Two-Lane Blacktop

Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) has a cool, distinctive vision of America that’s both post-hippie and pre-counterculture; the young anti-heroes, though two are played by musicians, seem rather apathetic to drugs and rock’n’roll. James Taylor and Laurie Bird share sexual vibes, but this love ain’t free—though, for the hitchhiking teenager Bird, love often appears to be. For the mechanic, played by Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, life only seems to exist beneath a car’s hood. Then there’s Warren Oates, the rambler in his G.T.O., who seems snowed in by his life experiences (he has lived twice as long as the others); he has the most human dimensions, but seems like a mythological shape-shifter: He’s so uncomfortable with himself that he puts on a smile and tells a new lie to every hitcher he picks up. Being an itinerant isn’t really a choice for him. When he picks up Harry Dean Stanton—whose voice warbles like Hank Williams’s, in piteous tones—and Stanton caresses G.T.O.’s leg, Oates shouts (hilariously!), “I’m not into that!” When Oates picks up a mustachioed hippie, who implies that a mysterious “we” have only thirty, forty years left (it being 2010 puts “us” in trouble), this pessimism makes Oates crumble; it rattles his phony enthusiasm and hits him too close to home. Nobody in this picture has a past or future; and since they keep on trucking, nobody really has a present, either. The “road” is a cheesy metaphor—even Hellman, in a D.V.D. feature, hates to “acknowledge the existential stigma this movie has to it”—but it’s a beaut here. Route 66—now an icon for nostalgists—is the road they’re taking cross-country, and if that’s not a bad omen, what is?

Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) has a cool, distinctive vision of America that’s both post-hippie and pre-counterculture; the young anti-heroes, though two are played by musicians, seem rather apathetic to drugs and rock’n’roll. James Taylor and Laurie Bird share sexual vibes, but this love ain’t free—though, for the hitchhiking teenager Bird, love often appears to be. For the mechanic, played by Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, life only seems to exist beneath a car’s hood. Then there’s Warren Oates, the rambler in his G.T.O., who seems snowed in by his life experiences (he has lived twice as long as the others); he has the most human dimensions, but seems like a mythological shape-shifter: He’s so uncomfortable with himself that he puts on a smile and tells a new lie to every hitcher he picks up. Being an itinerant isn’t really a choice for him. When he picks up Harry Dean Stanton—whose voice warbles like Hank Williams’s, in piteous tones—and Stanton caresses G.T.O.’s leg, Oates shouts (hilariously!), “I’m not into that!” When Oates picks up a mustachioed hippie, who implies that a mysterious “we” have only thirty, forty years left (it being 2010 puts “us” in trouble), this pessimism makes Oates crumble; it rattles his phony enthusiasm and hits him too close to home. Nobody in this picture has a past or future; and since they keep on trucking, nobody really has a present, either. The “road” is a cheesy metaphor—even Hellman, in a D.V.D. feature, hates to “acknowledge the existential stigma this movie has to it”—but it’s a beaut here. Route 66—now an icon for nostalgists—is the road they’re taking cross-country, and if that’s not a bad omen, what is?While seconding Hellman’s reluctance to broach existentialism—though, in a way, it’s there, just as it’s present in so much else—I think this film compares to Hiroshima, Mon Amour, Alain Resnais’s beautiful avant-garde poem of about a dozen years earlier. The stories are completely different, and so are the narrative techniques, but they both hit on that lack of a present timeframe. In the French film, time is garbled by flashbacks to emotions that still feel fresh; here, we haven’t anything to flash back to. It’s about the perils of living in the moment. Blacktop came out the same year that Hunter Thompson wrote about the wave of youth and freedom cresting in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The counterculture’s awareness of its own demise is palpable, almost bitter, here—in a way that it wasn’t in the euphoric Bonnie and Clyde, four years earlier. (Some critics compared this film to the recent George Clooney vehicle The American, but despite the drag-racing, Blacktop exists on its own—without pulp. The American wraps its “art” not around something that’s dying, but something that’s always been, aesthetically speaking, dead.) But, to look back on Blacktop from this vantage—writing on a laptop, publishing on the internet, driving on long, anonymous freeways from which every town looks the same—there’s enough long hair to make one feel nostalgic. We’re witnessing a moment the filmmakers already thought was gone.

Monday, September 6, 2010

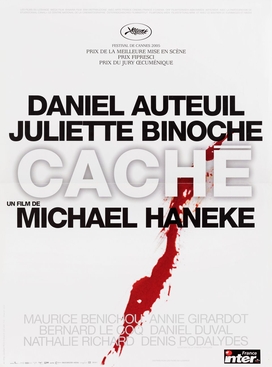

Caché

Michael Haneke’s Caché is about white guilt, French division. You can tell early on that the mystery of the videotapes—à la Lost Highway—will never be solved, and that there’ll be no chance for Daniel Auteuil’s Georges to redeem himself. The tapes are just a ploy to strip him naked, to show that beneath the veneer of civilization—he hosts a show about books on public television, and his wife works in publishing—he’s a petty, pathetic man, still held accountable for a crime he committed at age six, a crime that he’ll never have the humility to fess up to. Haneke’s “objective” style has the same objectives as the videotapes. In The White Ribbon, set nearly a century ago, his dreamlike, black-and-white formalism captured how things might have felt; in Caché, he seems to be saying that this is how things are. Everybody—even refined literary types (the sort who’d go to see such a high-minded thriller)—is stained. It might have been more tolerable if Georges went through some semblance of a change, but Haneke makes it clear that, outside of his nightmares, Georges will never budge. To him, the mystery has been solved, even as it’s made abundantly clear to us that he’s latching onto a red herring—an improbable one at that. But the film is certainly gripping; you suffer on Georges’s behalf.

Friday, September 3, 2010

Tokyo Story

Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story is stately; it was made in 1953, but feels much older. I think this has less to do with the cultural divide than it does the gulf between the ages. Though the movie is considered one of the greatest works of world cinema, and carries you along with a strange, becalming, old-world serenity, it seems to raise issues that it refuses to confront. This can partly be explained as reflective of the way the family it depicts interacts, but that isn’t quite satisfactory; the film is about moving on, but it moves on too easily, with so much left up in the air. It’s too tidy to be ambiguity; it must be underdevelopment. All the conflicts seem benign, as if elucidation was not required. The elderly father is disappointed in his son, a neighborhood doctor. Why? He should be doing better things than helping the sick? Their relationship goes completely undefined. Unlike a recent family-reunion movie, A Christmas Tale, the filial dynamics here haven’t the weight of history; except in the case of one daughter—a bitchy beautician who looks like Mary Tyler Moore in Ordinary People—it’s hard to imagine what life was like when the kids were growing up and living under the same roof in provincial Onomichi. We can’t really determine why the old couple’s daughter-in-law, whose husband has died (in World War II?), is so selflessly kind to them. Is it because she’s still carrying their son’s torch? Is it some guilt that’s been carried over? Perhaps it’s her kinship with the old man: They both have strange, impersonal smiles—like flight attendants’. Some sort of emotions are being repressed, but which? The revelation that Father was a souse, and may become one again soon, makes his placidity seem a touch sinister. Father calls Mother headstrong, but she isn’t really. They only fight once, in the very beginning—and, in retrospect, that seems a false start. But Chieko Higashiyama, who plays Mother, is a true focal point. She’s the movie’s soul. Unlike everyone else, she seems acutely aware of the undercurrents that the others are sitting cross-legged on top of. She looks as though she’s spent her life waiting for these feelings to be uncovered, but she ends up dying in vain; her passing is made to symbolize the end of an era.

Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story is stately; it was made in 1953, but feels much older. I think this has less to do with the cultural divide than it does the gulf between the ages. Though the movie is considered one of the greatest works of world cinema, and carries you along with a strange, becalming, old-world serenity, it seems to raise issues that it refuses to confront. This can partly be explained as reflective of the way the family it depicts interacts, but that isn’t quite satisfactory; the film is about moving on, but it moves on too easily, with so much left up in the air. It’s too tidy to be ambiguity; it must be underdevelopment. All the conflicts seem benign, as if elucidation was not required. The elderly father is disappointed in his son, a neighborhood doctor. Why? He should be doing better things than helping the sick? Their relationship goes completely undefined. Unlike a recent family-reunion movie, A Christmas Tale, the filial dynamics here haven’t the weight of history; except in the case of one daughter—a bitchy beautician who looks like Mary Tyler Moore in Ordinary People—it’s hard to imagine what life was like when the kids were growing up and living under the same roof in provincial Onomichi. We can’t really determine why the old couple’s daughter-in-law, whose husband has died (in World War II?), is so selflessly kind to them. Is it because she’s still carrying their son’s torch? Is it some guilt that’s been carried over? Perhaps it’s her kinship with the old man: They both have strange, impersonal smiles—like flight attendants’. Some sort of emotions are being repressed, but which? The revelation that Father was a souse, and may become one again soon, makes his placidity seem a touch sinister. Father calls Mother headstrong, but she isn’t really. They only fight once, in the very beginning—and, in retrospect, that seems a false start. But Chieko Higashiyama, who plays Mother, is a true focal point. She’s the movie’s soul. Unlike everyone else, she seems acutely aware of the undercurrents that the others are sitting cross-legged on top of. She looks as though she’s spent her life waiting for these feelings to be uncovered, but she ends up dying in vain; her passing is made to symbolize the end of an era.That era, of course, is prewar Japan. The elderly couple are like fish out of water in their nation’s capital. It’s a metropolis to them, though—to modern viewers, aware of how cosmopolitan Tokyo has since become—it seems like a second-class city in the Rust Belt. Ozu’s style is partly to blame. He focuses on straight lines and right angles; all of his static camerawork is intricately worked out—in a way, masterful. But, except for a few shots of traditional architecture at the end, the cramped Tokyo interiors don’t look much different from the Onomichi homestead. And even when things are “lively,” his pace remains the same; it’s vibrance as seen from an objective point of view, one which never differs, and is at cross-purposes with the movie’s insistence that things change. Universal as the theme is, I don’t respond so well to the caveat that things invariably change for the worse. There’s a touch of quietism in how Ozu appears to see things: Children grow apart from their parents, but children also become worse people, necessarily selfish, and the process is inevitable. Even the daughter-in-law admits that she’ll be subject to it—despite herself. Mother is an externalization of Ozu’s style; that’s why she’s the one to die.

Still, Tokyo Story must be judged as a product of its time. It seems to be a Japanese equivalent of Dickensian England—at the end of an era in which members of a family live out their lives in an ancestral home, and yet before the advent of true mass communication. One gets the impression that the old couple hardly sees their children, and do not talk to them frequently. For emergencies, they still send telegrams; the house in Onomichi probably doesn’t have a telephone. No wonder their visit to the city seems so momentous. If nothing else, the bucolic gotham of this film lends perspective to Kurosawa’s High and Low of ten years later. Though I thought that movie was a bit too procedural, and that it wore its themes on its sleeves, the gap between it and Tokyo Story says a lot about Japanese growth and urbanity in the middle of the twentieth century. No wonder that the nightlife scrutinized by the Kurosawa film looked like a wild Westernization. And it isn’t very hard to grasp Tokyo Story’s enduring appeal. It makes the increasing complexity of the world feel simpler. It looks at the future with eyes from the past, and its staunch, ascetic serenity reminds one that some values will never change.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)