Ben Affleck's The Town is a movie I wanted to like more than I did. I did like it; there's no question that as a director, and as an actor, Affleck is earnest; and it's hard to not feel a certain affection for his character. But the dramatic arc goes haywire. He hardly flinches when he tries to pick up the woman he held hostage during a robbery (Rebecca Hall), and she hardly flinches when the FBI guy (Jon Hamm) tells her the truth about Affleck. He doesn't even give himself a moment to register the truth when a gangster reveals that his mother, presumed missing, was murdered. The director puts the brake on scenes too early, and plot threads simply don't tie together. The romance looms large early on, and one wants to see Hall and Affleck stay together; but Jeremy Renner, as Affleck's psychopathic accomplice, isn't a threat to their love for long. Renner is a fantastic actor when he gets to be intense and this movie gives him plenty of excuses for that. But what is one to make of this townie pscyho with a heart of gold? He has a great moment when he slurps the remainder of his drink before facing his final hail of gunfire from the FBI, but I was hoping for a little more Tommy Udo in him. He has too much "depth" when he should be simplistically frightening; and yet every other character is cardboard. Hall is stuck with the "love interest from out of town" label, and though Hamm's mannerisms are familiar, he tries to carve a prick out of his potentially dirty G-man. But Affleck is the only one with any substance, any hidden motivations. And the obstacles that require him to take on one last heist stack up too easily. Gone Baby Gone felt like the dime-novel mystery that it was, but Affleck seems to have made less with the more human material that The Town comprises. He doesn't come on as strongly with his hometown affection here, though one feels good at witnessing this love letter to a semi-anachronistic side of a city which is generally perceived in terms of wealth and history and Harvard and MIT. But the robbery scenes never go beyond average, and with the narrative ride as bumpy as it is, all one's left with is the Boston cream filling.

Ben Affleck's The Town is a movie I wanted to like more than I did. I did like it; there's no question that as a director, and as an actor, Affleck is earnest; and it's hard to not feel a certain affection for his character. But the dramatic arc goes haywire. He hardly flinches when he tries to pick up the woman he held hostage during a robbery (Rebecca Hall), and she hardly flinches when the FBI guy (Jon Hamm) tells her the truth about Affleck. He doesn't even give himself a moment to register the truth when a gangster reveals that his mother, presumed missing, was murdered. The director puts the brake on scenes too early, and plot threads simply don't tie together. The romance looms large early on, and one wants to see Hall and Affleck stay together; but Jeremy Renner, as Affleck's psychopathic accomplice, isn't a threat to their love for long. Renner is a fantastic actor when he gets to be intense and this movie gives him plenty of excuses for that. But what is one to make of this townie pscyho with a heart of gold? He has a great moment when he slurps the remainder of his drink before facing his final hail of gunfire from the FBI, but I was hoping for a little more Tommy Udo in him. He has too much "depth" when he should be simplistically frightening; and yet every other character is cardboard. Hall is stuck with the "love interest from out of town" label, and though Hamm's mannerisms are familiar, he tries to carve a prick out of his potentially dirty G-man. But Affleck is the only one with any substance, any hidden motivations. And the obstacles that require him to take on one last heist stack up too easily. Gone Baby Gone felt like the dime-novel mystery that it was, but Affleck seems to have made less with the more human material that The Town comprises. He doesn't come on as strongly with his hometown affection here, though one feels good at witnessing this love letter to a semi-anachronistic side of a city which is generally perceived in terms of wealth and history and Harvard and MIT. But the robbery scenes never go beyond average, and with the narrative ride as bumpy as it is, all one's left with is the Boston cream filling.Thursday, September 15, 2011

The Town

Ben Affleck's The Town is a movie I wanted to like more than I did. I did like it; there's no question that as a director, and as an actor, Affleck is earnest; and it's hard to not feel a certain affection for his character. But the dramatic arc goes haywire. He hardly flinches when he tries to pick up the woman he held hostage during a robbery (Rebecca Hall), and she hardly flinches when the FBI guy (Jon Hamm) tells her the truth about Affleck. He doesn't even give himself a moment to register the truth when a gangster reveals that his mother, presumed missing, was murdered. The director puts the brake on scenes too early, and plot threads simply don't tie together. The romance looms large early on, and one wants to see Hall and Affleck stay together; but Jeremy Renner, as Affleck's psychopathic accomplice, isn't a threat to their love for long. Renner is a fantastic actor when he gets to be intense and this movie gives him plenty of excuses for that. But what is one to make of this townie pscyho with a heart of gold? He has a great moment when he slurps the remainder of his drink before facing his final hail of gunfire from the FBI, but I was hoping for a little more Tommy Udo in him. He has too much "depth" when he should be simplistically frightening; and yet every other character is cardboard. Hall is stuck with the "love interest from out of town" label, and though Hamm's mannerisms are familiar, he tries to carve a prick out of his potentially dirty G-man. But Affleck is the only one with any substance, any hidden motivations. And the obstacles that require him to take on one last heist stack up too easily. Gone Baby Gone felt like the dime-novel mystery that it was, but Affleck seems to have made less with the more human material that The Town comprises. He doesn't come on as strongly with his hometown affection here, though one feels good at witnessing this love letter to a semi-anachronistic side of a city which is generally perceived in terms of wealth and history and Harvard and MIT. But the robbery scenes never go beyond average, and with the narrative ride as bumpy as it is, all one's left with is the Boston cream filling.

Ben Affleck's The Town is a movie I wanted to like more than I did. I did like it; there's no question that as a director, and as an actor, Affleck is earnest; and it's hard to not feel a certain affection for his character. But the dramatic arc goes haywire. He hardly flinches when he tries to pick up the woman he held hostage during a robbery (Rebecca Hall), and she hardly flinches when the FBI guy (Jon Hamm) tells her the truth about Affleck. He doesn't even give himself a moment to register the truth when a gangster reveals that his mother, presumed missing, was murdered. The director puts the brake on scenes too early, and plot threads simply don't tie together. The romance looms large early on, and one wants to see Hall and Affleck stay together; but Jeremy Renner, as Affleck's psychopathic accomplice, isn't a threat to their love for long. Renner is a fantastic actor when he gets to be intense and this movie gives him plenty of excuses for that. But what is one to make of this townie pscyho with a heart of gold? He has a great moment when he slurps the remainder of his drink before facing his final hail of gunfire from the FBI, but I was hoping for a little more Tommy Udo in him. He has too much "depth" when he should be simplistically frightening; and yet every other character is cardboard. Hall is stuck with the "love interest from out of town" label, and though Hamm's mannerisms are familiar, he tries to carve a prick out of his potentially dirty G-man. But Affleck is the only one with any substance, any hidden motivations. And the obstacles that require him to take on one last heist stack up too easily. Gone Baby Gone felt like the dime-novel mystery that it was, but Affleck seems to have made less with the more human material that The Town comprises. He doesn't come on as strongly with his hometown affection here, though one feels good at witnessing this love letter to a semi-anachronistic side of a city which is generally perceived in terms of wealth and history and Harvard and MIT. But the robbery scenes never go beyond average, and with the narrative ride as bumpy as it is, all one's left with is the Boston cream filling.Thursday, September 1, 2011

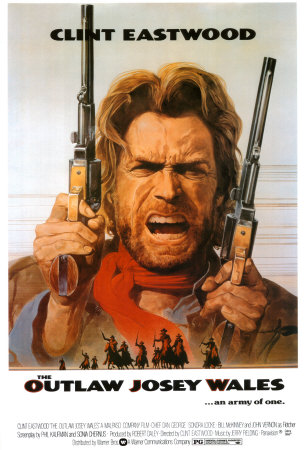

The Outlaw Josey Wales

Clint Eastwood's The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) is a compromise between the classical Western and the anti-Western, between the early Eastwood figure and his later directorial self. His early figure, despite the consistent veil of nonchalance, was actually split in two: The Man With No Name was the total mercenary, in the game only for money or survival (basically the same thing), and Dirty Harry was righteousness personified. Josey Wales hews more closely to the first. Even as the rest of his Confederate company defects at the end of the Civil War, he decides to go it on his own--not out of loyalty, and not for the cause, but mainly because he wants to be left alone. That is, he doesn't want to be the subject of any government; he identifies with dispossessed Indians and optimistic homesteaders, people who flee the constraints and trappings of civilization. In the old Westerns (like those of Ford and Hakws), Wales would've found his new home thanks to the Union Army's help; in the newer ones (like the Spaghetti Westerns or Little Big Man), he would've been implicated in making the Indians dispossessed. Here, he gets a little of both: "governments" are the killers (not just in wars, or in the way the Union guns down the surrendering Confederates, a rather garish touch. It's federal ninnies who put the bounty on Josey's head). Our hero first became bloodthirsty fighting for one government, and now he's only bloodthirsty because he's trying to get away from the other. The film has the facade of the traditional Western, but an underlying note of post-sixties anti-war/anti-authoritarian cynicism. Josey Wales is thus about "the right to be left alone": the subset of the American dream that, today, has devolved into an American delusion, but one that's forgivable when applied to the period in which this was set, when the countless factors that bind the world's population today either didn't exist or were worn thin by the vastness of the West. Even Orwell admitted that the Old West was one of the few historical frames in which men were truly free. Or was it just the inaccuracies of the Western genre that made him, and billions of others, think so? The implications of that "right" (privilege, really, but Americans love their entitlements) are often maliciously misapplied, though not in this film; Josey exercises it fairly, trading being left alone for settling down and leaving others alone. Even so, that doesn't mean that Josey Wales is not simplistic when compared to Unforgiven, which balanced its gunslinger's right to do as he pleased with that of his victims' right to survive. Josey identifies with dispossessed Indians, but black people don't seem to exist here, probably because that would mean a confrontation with historical facts, a confrontation with what Josey's army really was fighting for--and it wasn't universal liberty. The film is a sentimental fantasy, set at a time when such fantasies were permissible, and featuring a dry hero who counteracts the preachiness of a lot of Eastwood's later work. It isn't profound, but it's a beautiful Western--you wallow not just in the beauty of the setting or the beauty of the dream but in the freedom from feeling that either are affected.

Clint Eastwood's The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) is a compromise between the classical Western and the anti-Western, between the early Eastwood figure and his later directorial self. His early figure, despite the consistent veil of nonchalance, was actually split in two: The Man With No Name was the total mercenary, in the game only for money or survival (basically the same thing), and Dirty Harry was righteousness personified. Josey Wales hews more closely to the first. Even as the rest of his Confederate company defects at the end of the Civil War, he decides to go it on his own--not out of loyalty, and not for the cause, but mainly because he wants to be left alone. That is, he doesn't want to be the subject of any government; he identifies with dispossessed Indians and optimistic homesteaders, people who flee the constraints and trappings of civilization. In the old Westerns (like those of Ford and Hakws), Wales would've found his new home thanks to the Union Army's help; in the newer ones (like the Spaghetti Westerns or Little Big Man), he would've been implicated in making the Indians dispossessed. Here, he gets a little of both: "governments" are the killers (not just in wars, or in the way the Union guns down the surrendering Confederates, a rather garish touch. It's federal ninnies who put the bounty on Josey's head). Our hero first became bloodthirsty fighting for one government, and now he's only bloodthirsty because he's trying to get away from the other. The film has the facade of the traditional Western, but an underlying note of post-sixties anti-war/anti-authoritarian cynicism. Josey Wales is thus about "the right to be left alone": the subset of the American dream that, today, has devolved into an American delusion, but one that's forgivable when applied to the period in which this was set, when the countless factors that bind the world's population today either didn't exist or were worn thin by the vastness of the West. Even Orwell admitted that the Old West was one of the few historical frames in which men were truly free. Or was it just the inaccuracies of the Western genre that made him, and billions of others, think so? The implications of that "right" (privilege, really, but Americans love their entitlements) are often maliciously misapplied, though not in this film; Josey exercises it fairly, trading being left alone for settling down and leaving others alone. Even so, that doesn't mean that Josey Wales is not simplistic when compared to Unforgiven, which balanced its gunslinger's right to do as he pleased with that of his victims' right to survive. Josey identifies with dispossessed Indians, but black people don't seem to exist here, probably because that would mean a confrontation with historical facts, a confrontation with what Josey's army really was fighting for--and it wasn't universal liberty. The film is a sentimental fantasy, set at a time when such fantasies were permissible, and featuring a dry hero who counteracts the preachiness of a lot of Eastwood's later work. It isn't profound, but it's a beautiful Western--you wallow not just in the beauty of the setting or the beauty of the dream but in the freedom from feeling that either are affected.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)